Guest Post: As Harry Potter Turns Twenty, Let’s Focus on Reading Pleasure Rather Than Literary Merit

It’s 20 years on June 26 since the publication of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, the first in the seven-book series. The Philosopher’s Stone has sold more than 450 million copies and been translated into 79 languages; the series has inspired a movie franchise, a dedicated fan website, and spinoff stories.

I recall the long periods of frustration and excited anticipation as my son and I waited for each new installment of the series. This experience of waiting is one we share with other fans who read it progressively across the ten years between the publication of the first and last Potter novel. It is not an experience contemporary readers can recreate.

I recall the long periods of frustration and excited anticipation as my son and I waited for each new installment of the series. This experience of waiting is one we share with other fans who read it progressively across the ten years between the publication of the first and last Potter novel. It is not an experience contemporary readers can recreate.

The Harry Potter series has been celebrated for encouraging children to read, condemned as a commercial rather than a literary success and had its status as literature challenged. Rowling’s writing was described as “basic”, “awkward”, “clumsy” and “flat”. A Guardian article in 2007, just prior to the release of the final book in the series, was particularly scathing, calling her style “toxic”.

My own focus is on the pleasure of reading. I’m more interested in the enjoyment children experience reading Harry Potter, including the appeal of the stories. What was it about the story that engaged so many?

Before the books were a commercial success and highly marketed, children learnt about them from their peers. A community of Harry Potter readers and fans developed and grew as it became a commercial success. Like other fans, children gained cultural capital from the depth of their knowledge of the series.

My own son, on the autism spectrum, adored Harry Potter. He had me read each book in the series in order again (and again) while we waited for the next book to be released. And once we finished the new book, we would start the series again from the beginning. I knew those early books really well.

‘Toxic’ writing?

Assessing the series’ literary merit is not straightforward. In the context of concern about falling literacy rates, the Harry Potter series was initially widely celebrated for encouraging children – especially boys – to read. The books, particularly the early ones, won numerous awards and honors, including the Nestlé Smarties Book Prize three years in a row, and were shortlisted for the prestigious Carnegie Medal in 1998.

The criticism was particularly prolific around the UK’s first conference on Harry Potter held at the prestigious University of St Andrews, Scotland in 2012. The focus of commentary seemed to be on the conference’s positioning of Harry Potter as a work of “literature” worthy of scholarly attention. As one article said of J.K. Rowling, she “may be a great storyteller, but she’s no Shakespeare”.

Criticism of the literary merit of the books, both scholarly and popular, appeared to coincide with the growing commercial and popular success of the series. Rowling was criticized for overuse of capital letters and exclamation marks, her use of speech or dialogue tags (which identify who is speaking) and her use of adverbs to provide specific information (for example, “said the boy miserably”).

Criticism of the literary merit of the books, both scholarly and popular, appeared to coincide with the growing commercial and popular success of the series. Rowling was criticized for overuse of capital letters and exclamation marks, her use of speech or dialogue tags (which identify who is speaking) and her use of adverbs to provide specific information (for example, “said the boy miserably”).

Even the most scathing of reviews of Rowling’s writing generally compliment her storytelling ability. This is often used to account for the popularity of the series, particularly with children. However, this has then been presented as further proof of Rowling’s failings as an author. It is as though the capacity to tell a compelling story can be completely divorced from the way a story is told.

Writing for kids

The assessment of the literary merits of a text is highly subjective. Children’s literature in particular may fare badly when assessed using adult measures of quality and according to adult tastes. Many children’s books, including picture books, pop-up books, flap books and multimedia texts are not amenable to conventional forms of literary analysis.

Books for younger children may seem simple and conventional when judged against adult standards. The use of speech tags in younger children’s books, for example, is frequently used to clarify who is talking for less experienced readers. The literary value of a children’s book is often closely tied to adults’ perception of a book’s educational value rather than the pleasure children may gain from reading or engaging with the book. For example, Rowling’s writing was criticized for not “stretching children” or teaching children “anything new about words”.

Many of the criticisms of Rowling’s writing are similar to those leveled at another popular children’s author, Enid Blyton. Like Rowling, Blyton’s writing has described by one commentator as “poison” for its “limited vocabulary”, “colorless” and “undemanding language”. Although children are overwhelmingly encouraged to read, it would appear that many adults view with suspicion books that are too popular with children.

There have been many defenses of the literary merits of Harry Potter which extend beyond mere analysis of Rowling’s prose. The sheer volume of scholarly work that has been produced on the series and continues to be produced, even ten years after publication of the final book, attests to the richness and depth of the series.

A focus on children’s reading pleasure rather than on literary merit shifts the focus of research to a different set of questions. I will not pretend to know why Harry Potter appealed so strongly to my son but I suspect its familiarity, predictability, and repetition were factors. These qualities are unlikely to score high by adult standards of literary merit but are a feature of children’s series fiction.

reposted under a CC license from The Conversation![]()

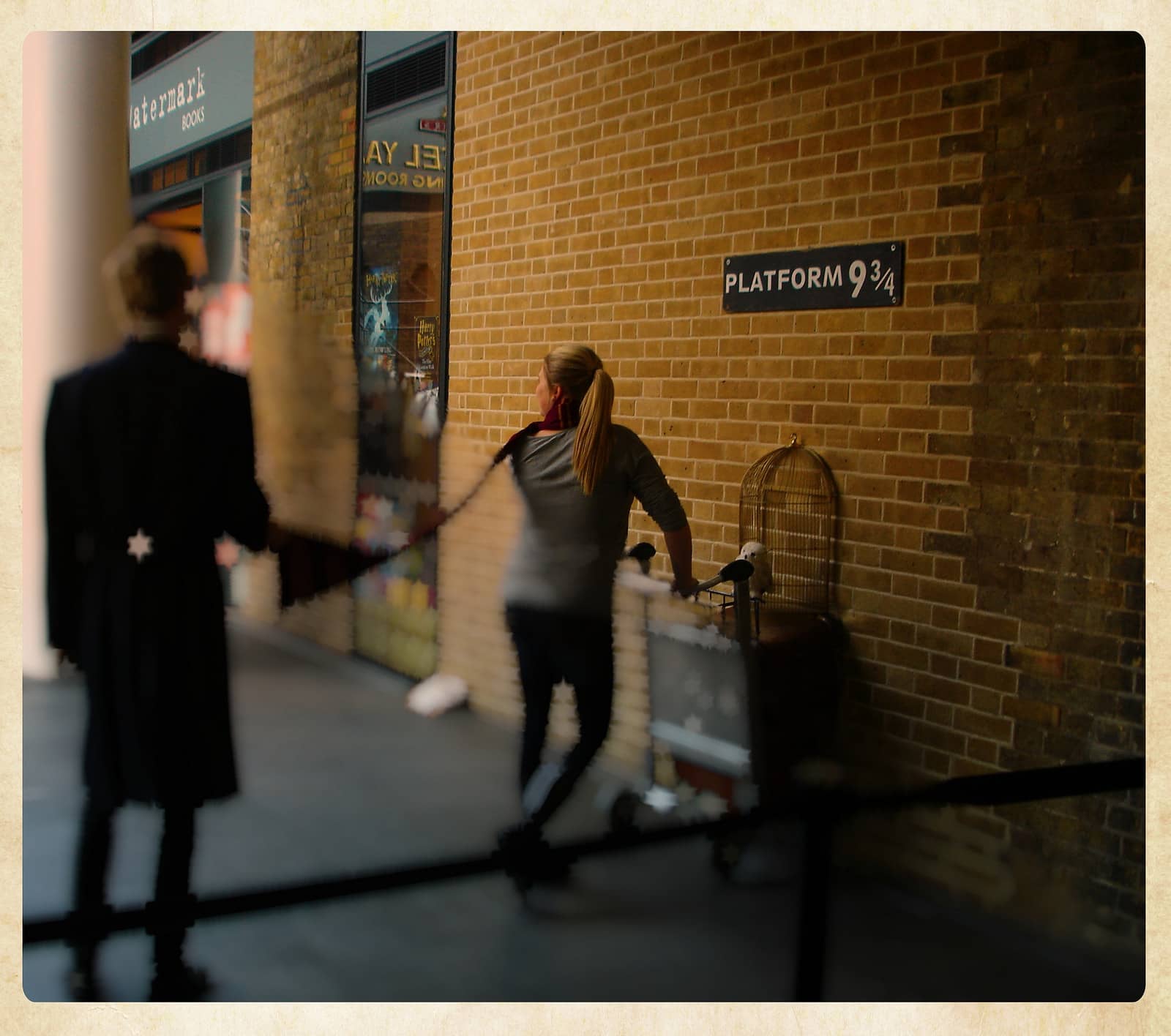

images by hans-jürgen2013, Alan Edwardes,

Comments

Joseph Sanchez June 21, 2017 um 12:21 pm

Let’s face it, Rowling is in no way a skilled or talented "writer". She is nowhere near as bad as Stephanie Meyer, but she is not a great writer, she is a storyteller with great characterization. Like other great storytellers she built a fully realized universe that developed a life and nature of its own, one of the greatest achievements any storyteller can attain. Those are literary qualities and achievements that should not be discounted or passed over because her writing was only adequate. Her writing did not hinder the story, the character development, the emotional connection, and the joy that comes from reading a good story. So we should give her the literary credit she deserves. Her writing talents are limited but did not hinder her from creating a beautiful and captivating universe filled with deeply compelling narratives and themes that transcended the story itself. This is one of the true marks of "literature".

Maria (BearMountainBooks) June 21, 2017 um 5:24 pm

What the hell is a skilled or talented writer if not one "who did not hinder the story, the character development, the emotional connection and the joy of reading a good story?" There isn’t much else left, so I’d just call her a great writer. She told stories people loved and connected with–the actual words, the order of the words, the choice of words–don’t matter. (I read books 1-3 and enjoyed all them although I thoroughly loved book 1). Everyone is entitled to their own view of what makes a great writer or a great story. I think her sales and fans have declared her a great writer.

Lemondrop June 22, 2017 um 9:16 am

snob.

Shari June 22, 2017 um 7:21 am

For me, the story is the only thing. I don’t care about "literary merit", or how many adverbs were used. If I’m worrying about the number of adverbs or about whether or not the book uses a "limited vocabulary", then the author has failed to tell the story.

tired June 22, 2017 um 1:44 pm

I would say that when Rowling feels the need to say that Snape said something maliciously, she lacks the confidence that the reader will recognize that there is malice conveyed in the dialogue’s tone.

The prose is terribly flat and poorly written in her adult mystery novels as well. I think that it is a mistake to say that poor quality prose is acceptable in a story for children. Let me give an example from another popular, but much better written series (Lemony Snicket):

“Everyone, at some point in their lives, wakes up in the middle of the night with the feeling that they are all alone in the world, and that nobody loves them now and that nobody will ever love them, and that they will never have a decent night’s sleep again and will spend their lives wandering blearily around a loveless landscape, hoping desperately that their circumstances will improve, but suspecting, in their heart of hearts, that they will remain unloved forever. The best thing to do in these circumstances is to wake somebody else up, so that they can feel this way, too.”

And here is a quote from Harry Potter:

“Did you like question ten, Moony?" asked Sirius as they emerged into the entrance hall.

"Loved it," said Lupin briskly. "Give five signs that identify the werewolf. Excellent question."

"D’you think you managed to get all the signs?" said James in tones of mock concern.

"Think I did," said Lupin seriously, as they joined the crowd thronging around the front doors eager to get out into the sunlit grounds. "One: He’s sitting on my chair. Two: He’s wearing my clothes. Three: His name’s Remus Lupin…”

I didn’t cherry pick the quotes, I just picked two that I thought were representative. Does poor quality prose detract from an otherwise good story? Yes of course, don’t pretend otherwise. Does it ruin the experience? No. The Harry Potter series is strong thematically, with compelling plot and character.

There is something to be said for a body of works that grip an entire generation. But there have been plenty of times in which lightning in a bottle was completely forgotten a few generations later. We will have to see fifty years from now (if we’re alive) if Harry Potter is still talked about and read.

Maria (BearMountainBooks) June 22, 2017 um 6:10 pm

There is nothing wrong with either of those examples. They are both quite readable–although I find Rowling’s easier to read and more engaging. Both create atmosphere. One is the dead of night, the other the school atmosphere of competition and barbs/teasing. I prefer the shorter sentences and tone Rawlings created. That is probably why I only ever read one Lemony Snicket book and found it good, but not engaging enough to try another. Beauty–and apparently good writing–is in the eye of the beholder.

Will Entrekin June 23, 2017 um 8:14 am

I would disagree here. I find the Lemony Snicket passage terrible. If every word and sentence of a story needs to either advance plot or reveal character, it fails on both levels. Also, it stands completely on its own, which might seem like a strength but I think is actually a weakness; why is it with the rest of the story at all?

The Harry Potter example both advances plot and reveals character, and further reveals character about a couple (you not only get the note that Lupin responded to James' sarcasm without any of his own, but you also get a good sense of the dynamic between the three characters). Also, "thronging" is a great verb.

Rae June 23, 2017 um 7:37 pm

The fact it survived twenty years and is still thriving is much better than most.

Will Entrekin June 22, 2017 um 2:12 pm

The idea that Rowling is a great storyteller but not a great writer is daft. The opening lines of the first novel are a masterful example of setting up not just the story but also its world and tone, and the language is wonderful; they have a terrific rhythm, and Rowling makes great choices. I’ve always loved, e.g., the "which made drills." — of all the things Grunnings could manufacture, "drills" is as funny a tool as it is a word choice.

If anything, I think the spots of weakness later in the series only highlight her strengths throughout, as well as the need for good editing. I get the sense that the middle books were rushed, though from a perspective of production and not creation — Bloomsbury dropped that ball.

Maria (BearMountainBooks) June 23, 2017 um 8:45 am

This says it all:

The idea that Rowling is a great storyteller but not a great writer is daft.

You nailed it in one sentence!

Bokusen June 26, 2017 um 9:05 pm

I agree with this article completely. Harry Potter was one of the first long book series which really engaged me growing up. It’s also worth noting that J.K. Rowling was a Classics major, which explains why I, having been exposed to Harry Potter beforehand, started having odd deja vu moments when I started reading Dickens' Great Expectations. I kept feeling like "Am I sure this isn’t J.K. Rowling’s lost novel or something?". The prose style was so uncannily familiar to me it felt superbly erie. I think reading Harry Potter gave me a lifelong love of Dickensian prose as a result, and I might not be alone. My non-Harry Potter reading classmates in high school had a lot more trouble with reading Dickens' work than those who loved the series. Even if it hadn’t had the curious side-effect of inadvertently endearing me to something with more literary merit, I still think that Harry Potter introduced lots of children to the joys of reading, and surely that deserves some praise at least.

I also find Harry Potter more deftly written then other books like "The Hunger Games" or the "Twilight" series, although I’m very grateful those series gave lots of people hours of reading pleasure which is commendable in the age of the internet and endless other possible entertainments.

All in all, the act of people reading what engages them makes them like reading. If someone dislikes Harry Potter then they shouldn’t read it, but I hope they find another book which gives them just as much enjoyment as reading Harry Potter gave me.

Tim Hare July 2, 2017 um 12:26 am

I’ve heard similar arguments levied against Stephen King. These authors must be doing _something_ right because many people enjoy reading their works. To me that is the important measure – do people _want_ to read the work? If so, then the author has merit.