HarperCollins, Open Road Media Gird Their Loins in Battle Over the eBook Rights to Julie of the Wolves

Nevermind the anti-trust lawsuit against Apple or the indie bookseller lawsuit against Amazon and the 6 major publishers; this lawsuit over the ebook rights for a 40-year-old children’s book could affect countless contracts that authors have signed with legacy publishers over the past half century.

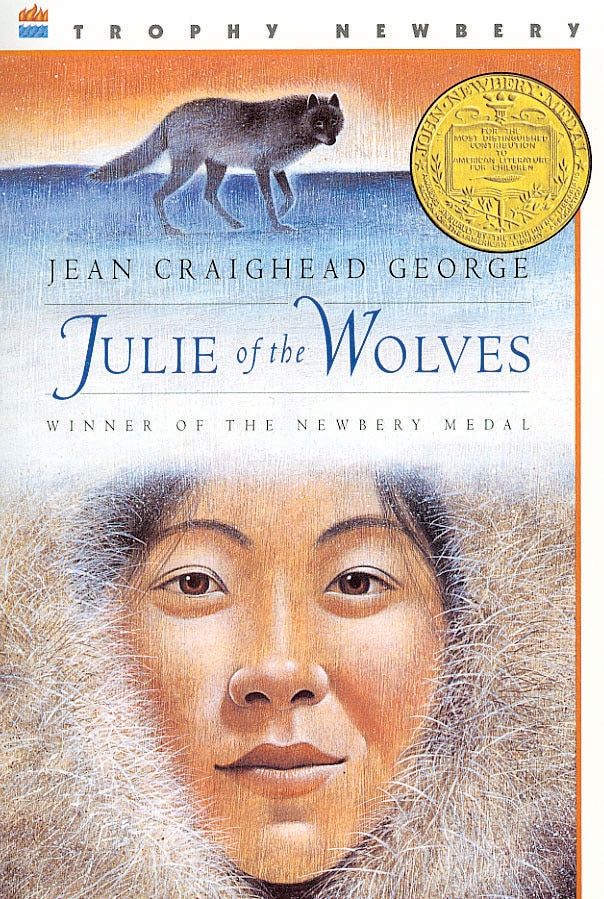

The story begins in 2011 when Open Road Media released the first ebook edition for Julie of the Wolves, Jean Craighead George’s bestselling children’s book. This book had been in print with HarperCollins since 1972, but only in paper.

About 4 months after Open Road publishes the ebook, HarperCollins files a lawsuit which claims that HarperCollins has held the ebook rights ever since the original contract was signed in 1971.

It has taken over a year, but this case is finally moving forward. A couple weeks ago Open Road and HarperCollins filed their motions for summary judgement. Each party has presented arguments explaining why the other party does not have a valid contract that covers the ebook rights.

Before I summarize the arguments, I want to point out one important detail that isn’t mentioned in the lawsuit but speaks volumes about the background for this case.

If HC had the ebook rights (like they claim) then why did they not release an ebook version of Julie of the Wolves 5 years ago or 10 years ago? There is a Kindle Edition, yes, but it was published by Open Road Media in August 2011.

Doesn’t the lack of an HC published ebook make you wonder if for many years they thought they didn’t have the ebook rights to this title? At the very least it makes me question why HC behaved like they didn’t control the ebook rights (right up until Open Road Media signed a contract with the author). What, do you really think HC left a classic and profitable title out of the Kindle Store simply because no one noticed? I don’t buy that argument.

This case hinges on how the judge will decide to interpret a couple paragraphs in the original contract that the author signed with HarperCollins over 40 years ago. First there is paragraph 23, which says “the Publisher shall have the exclusive right to sell, lease or make other disposition of the subsidiary rights in which he has an interest”. That’s a fairly common clause in publishing contracts with a well-defined meaning, but the text of paragraph 20 is not.

Here is paragraph 20 (from the HC motion):

Anything to the contrary herein notwithstanding, the Publisher shall grant no license without the prior written consent of the Author with respect to the following rights in the work: use thereof in storage and retrieval and information systems, and/or whether through computer, computer-stored, mechanical or other electronic means now known or hereafter invented and ephemeral screen flashing or reproduction thereof, whether by print-out, phot sic] reproduction or photo copy, including punch cards, microfilm, magnetic tapes or like processes attaining similar results…

HarperCollins points to the text of the paragraph and claims it covers electronic editions (including ebooks), while Open Road Media presents a counter argument that the text meant something completely different when the contract was signed in 1971.

HarperCollins is arguing that this paragraph mentions "storage and retrieval and information systems" as a right that HC needs to get written permission before granting a license, it means that HC has the ebook rights.

Open Road Media argues that this paragraph meant something entirely different when the author’s agent inserted it into the contract in 1971. Yes, you read that right; George’s agent is responsible for that paragraph. According to Open Road, this text was added because the agent foresaw that indexing and library systems might be a possible future market.

From the Open Road brief:

Beginning in the mid-1960’s (when Curtis Brown first inserted this clause in the contracts it negotiated for its authors), people were beginning to foresee using computers to analyze and search for information about books, essentially a far more sophisticated manner of retrieving information than the traditional Library of Congress card catalogue system. Curtis Brown wanted the authors to share in the proceeds if such a market for storage and retrieval systems actually did develop.

Open Road goes on to cite 8 different scholarly articles, textbooks, and reference books that focus on storage, information retrieval, and related topics. These sources, published between 1965 and 2012, show that the common usage of the terms mentioned in paragraph 20 is in no way related to ebooks.

Open Road also points out that HarperCollins updated their boilerplate contract in the 1990s and that the contract included 2 separate mentions of electronic rights: “verbatim electronic displays” and “information storage and retrieval systems.” Guess which one refers to ebooks? Hint: it’s not the term used in the contract with George.

I was not expecting this lawsuit to be so open-and-shut, but Open Road offers a compelling set of arguments that shoot down every possible misinterpretation that HarperCollins could present.

HarperCollins wants the court to believe that the ebook market could have been foreseen in 1971. If that is the case then why didn’t HC add a clause to their standard contract? And why did they use different language 20 years later?

It looks to me like the HC lawyers are twisting the original contract into a pretzel. Let’s hope they don’t succeed. If they do then they will be able to pull off a land grab for ebook rights the likes of which have not been seen before.

If this case is decided in favor of HarperCollins it will have an effect an the ebook market of a magnitude that we have not seen since the 2001 court case Random House vs Rosetta Books. As you might recall, Rosetta Books won the case because the judge ruled that the contract term "in book form" did not include ebooks. The case was eventually settled out of court (rather than go through multiple rounds of appeals) with terms that were not made public, but one obvious outcome was that Rosetta Books continued to publish the ebooks.

If Random House had won that case then virtually every existing contract between author and publisher would have been assumed to cover ebook rights – no matter whether or not ebooks were mentioned. The case between HarperCollins and Open Road is going to have a similar effect should HarperCollins win.

Comments

Gary March 31, 2013 um 9:01 pm

I am not a lawyer. I am not an expert in the copyright laws in any country.

If I were the judge in this case I would throw the Harper Collins suit out of court on the first day. As far as I am concerned, the words "the Publisher shall grant no license without the prior written consent of the Author" means that the author owns those rights, not the publisher. The publisher can negotiate with another party, and arrive at terms, but they have to go back to the author for "permission" and, unstated but obvious, is the condition that the author has to be made happy (i.e. paid) before the author will grant such permission.

If the publisher "owned" the rights, they would not have to get permission to exercise them.

Stumbling Over Chaos :: Linkity wishes the damn “T” key would stay where it’s supposed to April 5, 2013 um 8:04 pm

[…] Julie of the Wolves and the battle for ebook rights. […]

The Recent Tintin Ruling Offers a Valuable Reminder that Creators Need to Understand the Contracts They Sign | Ink, Bits, & Pixels June 17, 2015 um 9:31 am

[…] is a replay of the 2013 court battle over the ebook rights to Julie of the Wolves, only on a much larger scale. In that earlier case […]