Hong Kong Copyright Battle Tests US Candidates' Commitments to Free Speech

Although this bill normally would not have caught global attention, the government’s active push for new criminal penalties shortly after the first anniversary of massive citywide pro-democracy protests has raised free speech and civil liberties concerns. These concerns were heightened when a bookseller of banned Chinese books mysteriously disappeared two days before the New Year, and then four additional booksellers disappeared in the following week.

Hong Kong’s controversial copyright bill also presents policy challenges for the U.S. government. Although this former British colony became part of China in 1997, its practice of “one country, two systems” has made it strategically important. How this special administrative region protects freedom and democracy – and, for that matter, intellectual property – will inevitably have serious ramifications on the mainland.

To some extent, the controversy has posed an unexpected test for U.S. presidential candidates. Should they support copyright reform abroad that will help protect American music, movies, TV programs and computer software? Or should they stand alongside the protesters, many of whom were among those demanding democratic reforms a year ago?

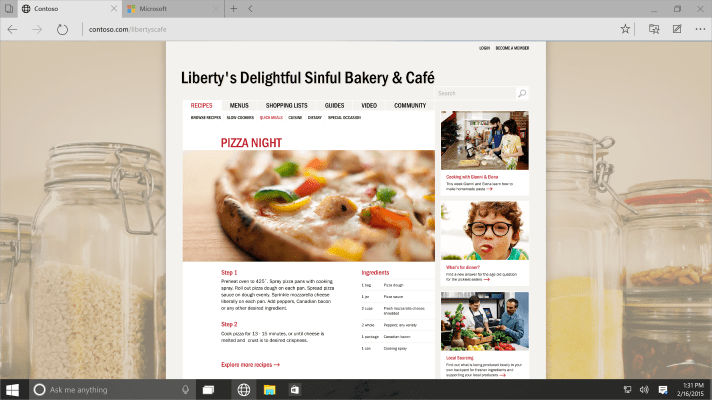

Hong Kong people fight for Internet freedom outside the Legislative Council. Reuters

Hong Kong people fight for Internet freedom outside the Legislative Council. ReutersTwo strange bedfellows

When free speech and copyright protection get together, they make strange bedfellows. People tend to assume that copyright protection is in harmony with free speech. The U.S. Supreme Court even declared that copyright is intended to be “the engine of free expression.”

Yet, intent is not the same as reality. Because copyright laws rapidly expanded in the past two decades, they now cover many online activities, including political and quasi-political communication. Whether free speech and the democratic discourse will remain protected will depend on how copyright laws are being enforced.

Indeed, the fair enforcement of these laws is at the heart of the current protests in Hong Kong. Local netizens are protesting not because they want to support large-scale online copyright piracy. Rather, they genuinely worry that many of their communicative and expressive activities will be caught in the net, attracting criminal prosecutions, civil lawsuits and selective enforcement.

A controversial bill

The proponents of the copyright bill claim that Hong Kong needs stronger protection to target illegal streaming of movies and TV programs. Yet, they have a tough time explaining why the bill was drafted so broadly to cover all forms of electronic communication. They also fail to alleviate the netizens' concerns about unnecessary criminal penalties and potential government abuse.

Although the bill includes fair dealing exceptions for parody, satire, caricature, pastiche, quotation and commenting on current events, these exceptions are narrow and laden with conditions. All of them also require prosecutors and courts to do case-by-case balancing.

Considering the strong distrust many Hong Kong people have of their government, it is not difficult to see why they fear that the new law will become just another secret weapon to silence dissent. Their fears are also understandable following the government’s active – and, in their view, selective – prosecution of peaceful protesters of the “Occupy Movement.”

U.S.-China policy

Thus far, the controversy surrounding Hong Kong’s copyright bill has presented an unwanted policy dilemma for the U.S. government.

On the one hand, stronger online copyright protection in Hong Kong may pave the way for similar reforms in China. Such reforms are important because the Internet has become a crucial entry point for American media products to enter the Chinese market – due largely to censorship in traditional channels, such as cinemas and DVDs.

On the other hand, freedom and democracy are of paramount importance to Americans. Many see freedom as the raison d’être of the U.S., and China as the antithesis of the free world. Thus, the more freedom and democracy Hong Kong has, the more likely the region’s reforms are to percolate into other parts of China.

The dilemma between these two very different policy goals was made salient when the local U.S. consulate and the American Chamber of Commerce were caught reaching out to pro-Beijing legislators to push for the controversial copyright bill. Not only were the local mass media perplexed by this unusual alliance, pro-democracy legislators also felt betrayed.

The way forward

Given this rather complex and delicate situation, how can the U.S. government promote American copyright interests without dampening the local people’s democratic aspirations?

The easiest way out is, of course, to support a broad, open-ended exception, similar to the U.S. fair use doctrine. Such an exception is already included in a proposal advanced by pan-Democrat legislators in Hong Kong.

As of this writing, both the Hong Kong government and local copyright industries have vehemently opposed this proposal. Yet, the U.S. government has refrained from expressing support, notwithstanding the proposal’s American origin and strong pro-democracy appeal.

An alternative solution is to support the introduction of an exception that will prohibit civil and criminal actions against individual Internet users for noncommercial copyright infringement.

This exception is similar to existing U.S. copyright law, which prohibits infringement actions involving noncommercial audio recordings. An exception for the creation and distribution of user-generated content can also be found in the new Canadian copyright act, which further caps the damage awards for noncommercial infringement.

A collision course

When copyright protection collides with freedom and democracy, there is no easy way out. Yet, it is both naïve and irresponsible to assume that the same copyright laws can be enacted anywhere in the world without adjustment regardless of local political conditions.

The Occupy Movement awakened many Hong Kong people more than a year ago. It is high time the region developed a robust, critical and wide-open public debate. As much as the U.S. government needs to enhance intellectual property protection abroad, it should do so without sacrificing democratic advancement.

reposted under a CC license from The Conversation

images by mokastet, Reuters

No Comments